We are communities of the Nasa people of northern Cauca, Colombia, who since 2005 have stood up to the capitalist power that enslaves Mother Earth: "...our mother is not free for life, which she will be when she returns to being the soil and collective home of the peoples who care for her, respect her and live with her, and as long as this is not the case, neither are her children free. All the peoples are slaves along with the animals and the beings of life, as long as we do not get our mother to regain her freedom."

| Authors | Patricia Botero Gómez; Rita Valencia |

|---|---|

| Topics | Decolonization |

| Case Report | Volume 1: "Resilience in the Face of COVID-19" |

Brief description

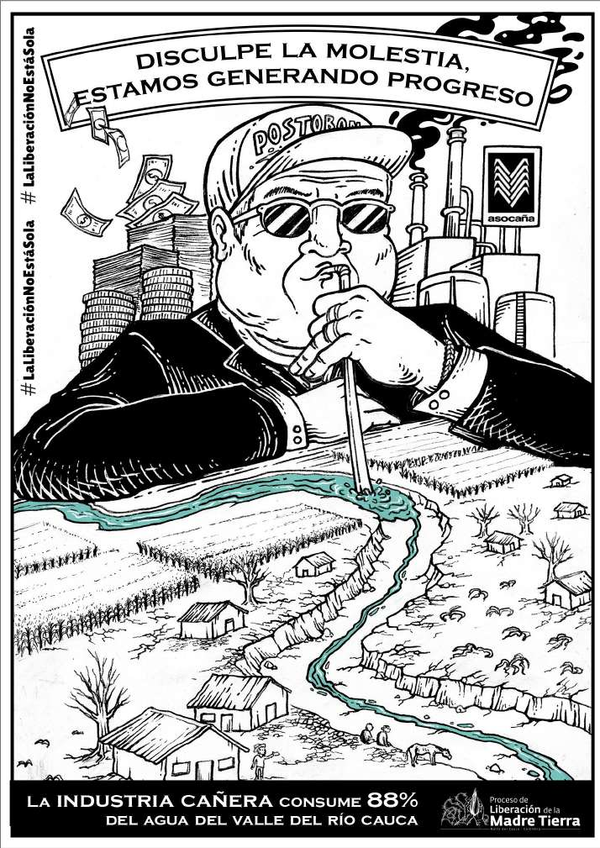

In Colombia, 0.4 percent of landowners own of the land, 25 million hectares of land are sanctioned for mining, and glaciers have lost 85 percent of their ice. Sugarcane occupies 330 thousand hectares of land in the Cauca River Valley and uses 25 million litres of water per second (Laing, 2018)[1] . It is for this reason that the indigenous Nasa people (from the North of Cauca, Colombia) say, “Our mother is not free to live...all of us are slaves along with the other beings until we don’t recover our mother’s freedom” (Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra, 2016)[2].

This is the collective vision of Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra, or the Process of Liberation of Mother Earth (PLMT), a movement that emerged from the North of Cauca, Colombia. It has emanated from the indigenous Nasa people, who, similar to many indigenous communities on this continent, have suffered dispossession through war and genocide. Their ancestral territories have been inflicted with violence—they have been confined within indigenous reservations with the permanent threat of ceasing to be what they are. However, the Nasa people have continued to resist. These millenarian guardians are caretakers of the territories of life. Their struggle is not only about redistribution of land but also about healing the land (Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra, 2005)[3].

The PLMT has emerged from a long path of struggle and resistance which has been going on for more than five hundred years. Since 2005, the PLMT has worked to restart direct action and struggle for land in Cauca. The struggle is about reconstitution and recovery of territories and with this, it aims to liberate Mother Earth. This territory is largely occupied as private property—‘slavery’ here is reflected by the intensive monoculture of sugarcane. As a by-product of the Green Revolution, large- scale industry-intensive production of sugar and ethanol has resulted in massive depletion of underground water reserves. In 2008, about 90 percent of water used for sugarcane cultivation in Cauca Valley came from surface water sources and 20,000 year-old reservoirs of water by digging wells that were 450 metres deep (Laing, 2018)[1].

Process that led to the community being resilient (Pre-covid)

In order to push ahead with the Nasa people’s struggle, the PLMT began occupying and liberating the private farms through organised mingas to cut sugarcane. Minga refers to collective work—in this ancestral practice, nobody is paid because working together is an act of celebration that holds the communitarian spirit alive. This has been just one part of liberation. The community has also continued with other long- term minga exercises: Cultivating corn, cassava, bananas, beans, growing vegetable gardens and practicing cattle grazing which helps in pulling out the roots of sugarcane (so that they do not sprout again with the next rain). But growing food and bringing water back to the springs are not easy tasks. The land is tired and eroded after so many years of damage done by harmful technology and the chemically-intensive packages of the Green Revolution. However, these are still not the biggest challenges faced by the community.

In December 2014, the community entered the first private farm to reoccupy it through collective organising in Corinto, a town in Cauca. Since then, they have been attacked more than 300 times by the plethora of armed forces, i.e., the army, paramilitary, guerrillas and the militarised police known as the ESMAD (Mobile Anti-Riot Squads of the National Police). It is worth mentioning that in the liberated haciendas (farms), the army has positioned itself within the private farms, making it very clear that the forces of the State serve only to protect private property (Nasaacin, 2015)[4]. Twelve liberators have been killed in these attacks and six hundred have been wounded— some of them seriously.

If anyone knows and understands the meaning of resistance, it is the native and Afro-descendant people who have been walking on this path for centuries. The COVID-19 pandemic can be understood, in this context, as one ill more, because therein lies the unending memory of all the threats to life that they have had to overcome.

How resilience that was established has helped during the pandemic

In the middle of the nation-wide lockdown, the PLMT, through a process called Food March, collected parts of the harvest from all of their liberated farms and sent two truckloads of yucca, beans, squash, medicinal herbs and much more to the city of Cali and other urban areas. The community has done this twice since 2018, and this was the third Food March, or Pandemic March—as there is no pandemic that can stop the liberation of Mother Earth. The Nasa say that their struggles, and now COVID-19, has taught them to be strong and rooted, and from this rootedness, to dream of seeing Mother Earth free.

The PLMT has also implemented technologies to liberate Mother Earth and it is supporting the formation of Nasa Yuwe School to recover the mother tongue of local indigenous communities. During the pandemic, the PLMT’s radio programme Vamos al corte (Lets go to Court) has been broadcasting slogans to weave together the collective consciousness among all members of the community: “Sow to liberate”—“Under the cement is the food”—to liberate in ways that all beings can fit in a pluriversal world—“We require not only land for the people, but people for the land” (Radio Program PLMT, 2021[5]).

This is part of the process of recovering Mother Earth while continuing with collective farming. The most important intention is to recover and liberate the territory from monoculture, resist private accumulation, and regenerate biodiversity so as to allow life to become bountiful and resilient in times of ecological crises.

As the Nasa people say, “Neither confinement, nor hunger, nor the virus are something new; we have been enduring these disasters for five centuries that devastated our people. We are the survivors of viruses and wars. We have been caged for three centuries in corners called resguardos[note 1] while in the flatland, the agro-industry privileges sugarcane plantations that only serve powerful industries. We have endured long periods of famine while the rich in the city live in the midst of waste and throw us crumbs and say: These are your rights.”

Lessons learnt

The COVID-19 pandemic conjures up hundreds of thousands of humans dying worldwide. However, the announced disaster of the Plantationocene—climate change—will be of even more epic proportions for the web of life. In the face of this oppressive system, liberators make it clear that we are part of Mother Earth. They do this by resisting the occupational logic of the coloniser with their practices of re- inhabiting Mother Earth with care, reciprocity, and mutuality.

Over time, a symbiotic relationship among different creatures will be recovered, with humans occupying a part of it instead of trying to control everything on this land. Rooting oneself in local knowledge, reviving indigenous seeds, promoting cropping diversity, practicing convivial farming, and embodying ecological practices can help achieve food sovereignty and ecological sustainability. Healing ourselves from the pandemic implies breathing with liberated Mother Earth.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Laing, Duglas (2018). “Caña y ganado, economías insostenibles para el Valle” Santiago de Cali: Agencia de Noticias Univalle. Disponible en: https://www.univalle.edu.co/medio-ambiente/cana-y-ganado-economias-insostenibles-para-valle

- ↑ Palabra del Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra (2016). “Libertad y armonía con Uma Kiwe.” Norte del Cauca: Minga de comunicación Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra. P. 31

- ↑ Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra (2005). “Libertad para la Madre Tierra.” Numeral 7. Cauca. https://liberaciondelamadretierra.org/libertad-para-la-madre-tierra/

- ↑ Nasaacin (2015). La caña de azucar prima en la agricultura. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BefNM-VkiUk

- ↑ Proceso de Liberación de la Madre Tierra. (2021). "Vamos al corte: Trueque en Mosoco y fuerza en la laguna". https://liberaciondelamadretierra.org/vamos-al-corte-trueque-en-mosoco-y-fuerza-en-la-laguna/

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "mina" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Notes

- ↑ Indigenous reservations are a legal and socio-political institution of a special nature, made up of one or more indigenous communities, which, with a collective property title that enjoy the guarantees of private property, own their territory and are governed by the management of this and their internal life by an autonomous organization protected by the indigenous jurisdiction and its own regulatory system. (Article 21, Decree 2164 of 1995). https://www.mininterior.gov.co/content/resguardo-indigena